Beyond the AI Inflection Point

What happens when districts ban AI? Go all in? Try to find balance?

Follow one district down all three paths.

Shaping the Future of Education

The arrival and rapid adoption of generative AI (GenAI) has found us at a critical moment in the history of education. It’s a moment, and technology, that invites prophecies about the future of learning. These narratives tend to fall into two patterns. The first casts GenAI as a dire threat to student learning and cognition that will slowly erode students’ ability to think and create. The second imagines students using GenAI to support or even enhance their learning and development.

GenAI, and its impact on students, will most likely fall somewhere in between. Students will evolve their use of and relationship with AI over their school careers and lives, experiencing both costs and benefits. But while the future is always more complex than we imagine it, GenAI is here. Its presence requires school and district leaders, policymakers, and educators to reflect on the meaning, purpose, and structure of our schools. If we want to bend toward a future where students have the necessary skills and agency to determine their own paths, then schools have to take action.

GenAI’s presence requires school and district leaders, policymakers, and educators to reflect on the meaning, purpose, and structure of our schools.

To understand what’s at stake in how we meet this moment, we will follow the story of Central Schools, an imagined yet representative district in the United States. Their journey starts down one path from the fall of 2023 to the spring of 2027. Then it diverges, splitting into three possible paths that take Central to 2030.

To make sure the focus stays on the challenges schools face now, and not on the potentialities of GenAI or other AI technology, this story deliberately assumes that AI capabilities will stay roughly where they are with minor improvements. This means most users in Central Schools interact with large language models (LLMs) via chatbots, both off-the-shelf and adapted for education. These tools serve as audiovisual companions for conversation, tutoring, research, and coding. They hallucinate at varying rates.

By tracing Central's journey, and the pressures, decisions, and consequences along the way, we get a glimpse of the hard work required of schools to shape a better future for our students beyond the inflection point.

Editor’s Note: For simplicity’s sake, we will use “AI” from this point instead of distinguishing between GenAI and AI more broadly.

2023–2024: Central’s Shake-Up

For years, mid-sized Central Schools, which serves 4,500 students across six elementary schools, two middle schools, and two high schools, thought of itself as "right in the middle." Central was not a trailblazing district, but it was willing to adopt evidence-based technology and teaching methods when warranted. In the fall of 2023, however, the middle stopped feeling safe. AI had arrived.

Students didn't wait for permission to use it. In late 2022 and early 2023, they found ChatGPT and then SnapchatAI on TikTok, Discord, and YouTube. As with most technologies over the past decade, students brought AI into schools in their pockets—sparingly at first, and then all at once. AI's spread through Central's classrooms created a new reality, whether the teachers and administrators were ready or not.1

Central was not a trailblazing district, but it was willing to adopt evidence-based technology and teaching methods when warranted. In the fall of 2023, however, the middle stopped feeling safe. AI had arrived.

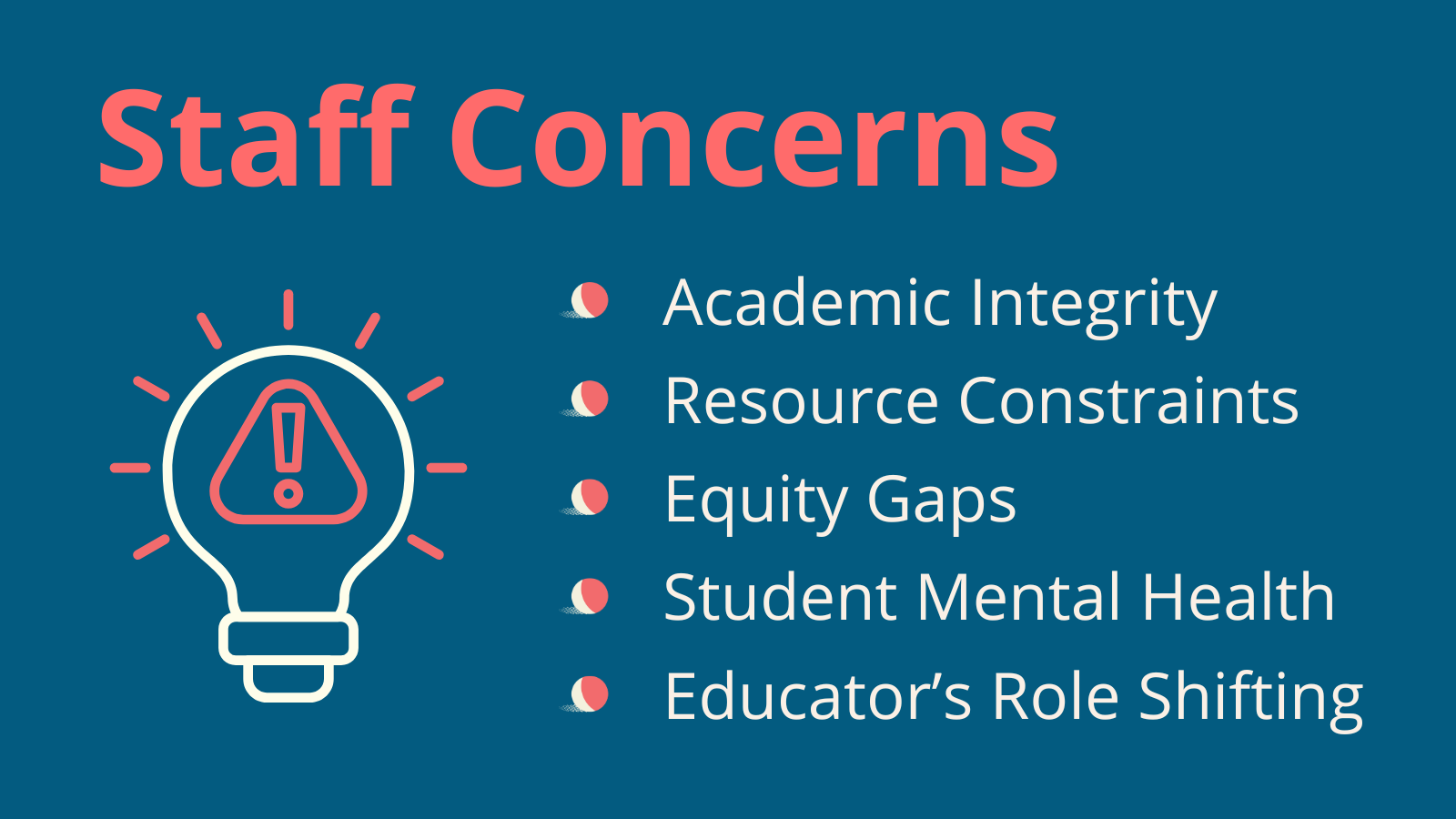

A new trend surfaced: A curious number of students showed improvement on homework and formative assignments but struggled on summative assessments. Teachers had limited insight into students’ thought processes and work, especially at home. Was students’ use of AI enabling learning or replacing it? While some students had family, friends, and social media helping them learn how to engineer prompts, evaluate responses, and refine AI outputs, others were left experimenting alone, with mixed results. Another group of students avoided AI entirely, worried about receiving inaccurate outputs or being labeled as cheaters. Teachers also overheard or observed students using AI chatbots for personal advice and emotional support.

AI usage and proficiency gaps widened between students. Those with fast home Wi-Fi and access to “pro” versions of AI tools were pushing the boundaries, building custom GPTs and learning how to generate writing, images, and code. Meanwhile, students with spotty connections and free AI tools struggled to use AI for much beyond homework help.2 The "digital divide" that Central had spent years trying to close had new fault lines.

AI and the Digital Divide

By Tanner Higgin

The arrival of AI has widened existing digital divides and created new fractures (Carter et al., 2020). While it’s fair and important to question the stakes of this divide, and the compulsion to adopt and use AI tools, there’s strong indication that employers are increasingly looking for workers with AI skills (“Beyond the Buzz,” 2025). For this reason alone, the divide between those with access to AI tools, and AI literacy, has potentially serious material consequences that can exacerbate existing inequities. Research indicates that, as has been the case with previous technologies, older people, women, and those with lower educational attainment and less tech access currently use AI less frequently (Suárez & García-Mariñoso, 2025 & Wang et al., 2025b). Additionally, LLMs and AI tools and platforms replicate harmful biases and engage in exclusionary practices that impact non-English speakers, people of color, and women (Lynch, 2025; Hofmann et al., 2024; AlDahoul et al., 2025). AI infrastructure, research, and global economic benefits are also cutting along existing lines, threatening to further solidify these exploitative divisions (Kitsara, 2022; Satariano et al., 2025).

In line with previous technological developments, combatting the emerging AI digital divide in schools is a fight across many fronts, including access, use, outcomes, and infrastructure (Bughin & van Zeebroeck, 2018; van Dijk, 2020). The “second-level” divide in particular, wherein the sophistication of technology use varies across populations, has been a well-documented struggle for schools integrating technology (Hargittai, 2002; Reinhart et al., 2011). One can imagine that this same phenomenon will happen with AI, an incredibly risky prospect given the known risks AI poses to cognition and mental health. Tackling this emerging AI literacy gap will require thoughtful policy, diligent implementation, nimble research, and the development of quality resources (Smith et al., 2025; Giuliano, 2025).

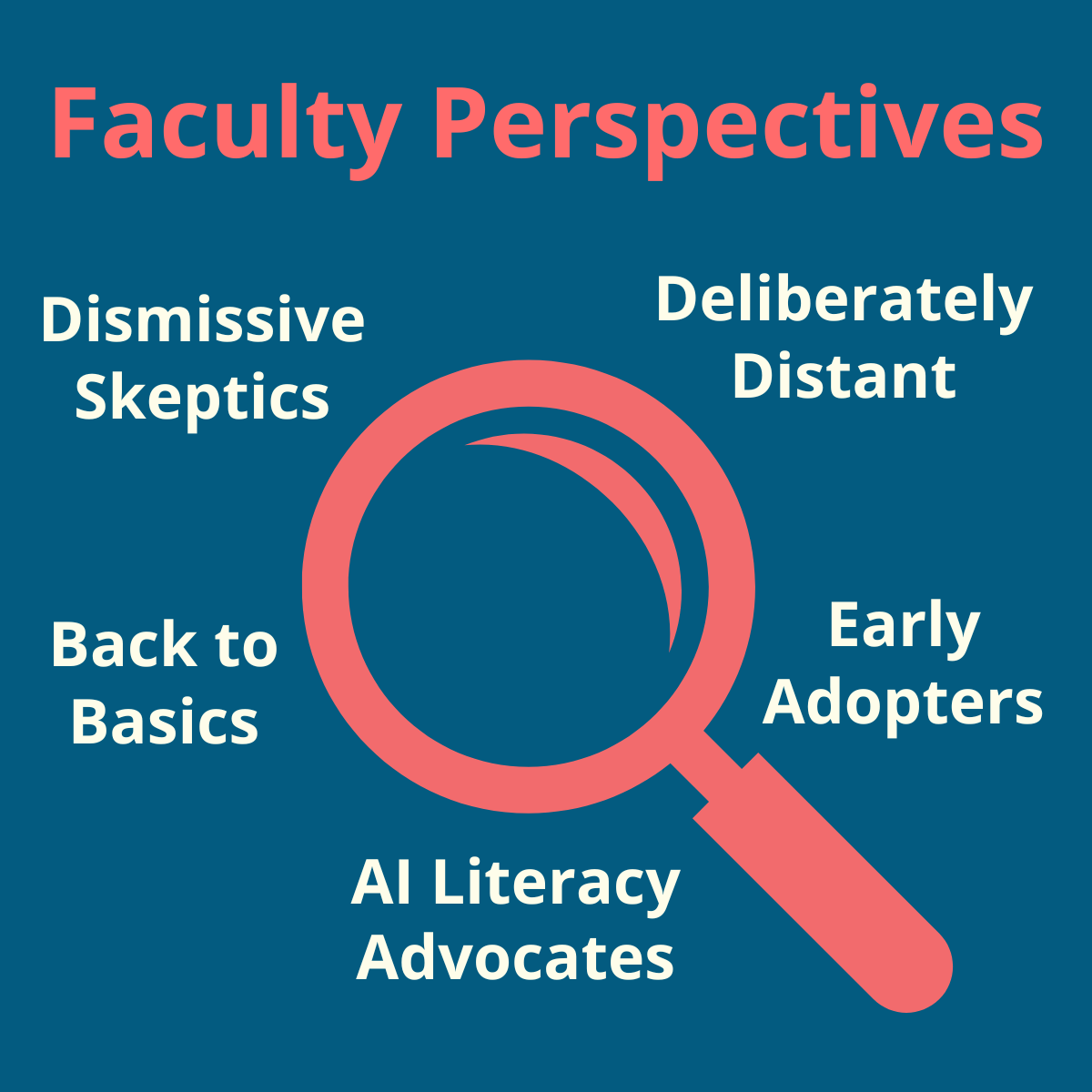

The faculty split into camps. Some thought AI was just another tool and not worth all of the hype, others argued that education would never be the same, and a few viewed AI as a threat to student privacy, academic integrity, and learning itself. Early adopters learned how to create differentiated instructional materials and parent newsletters faster. Elementary teachers approached AI cautiously, preferring to keep it at arm’s length. Many, especially those teaching K–2, saw it as irrelevant to their students. Most thought it was developmentally inappropriate to use with students. Several sounded the alarm about AI-enabled toys, however, and these teachers advocated for AI literacy for students, teachers, and parents. Special education staff were evenly divided; some saw potential for personalizing accommodations and supports, but others had questions about what student information was safe to share. High school teachers, especially those in English and social studies classrooms, began to question the authorship of every piece of writing that came in. Several teachers transitioned back to in-class, paper-and-pencil assessments. Teachers, already exhausted by policing phones, felt they now had to design and enforce their own policies around AI. Tensions among faculty rose, too. Some thought that AI was being adopted too quickly, putting academic integrity and student data at risk. Others claimed classrooms that didn’t incorporate AI left students at a disadvantage.3

Pressure from Central’s school board to address AI ramped up. Leaders realized that it was unwise to outright ban AI; however, effective implementation would require significant professional development, time, and resources—just as Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief Fund (ESSER) money was drying up.4

By spring 2024, the superintendent faced a big decision. Choosing a path forward would involve not just selecting which AI tools to use, but also defining Central's vision for AI adoption and then prioritizing any formal response among all of the district’s competing needs.

Key questions emerged:

- How much freedom should schools, teachers, and students have to select and use AI tools?

- How can Central keep student learning and development at the forefront?

- How might instruction and assessment need to change to account for AI’s capabilities and limitations?

- How can Central maintain trust and ensure the digital well-being of students and staff?

Looming behind all of these concerns was a deeply philosophical question: If AI would soon be able to complete most traditional assessments, how should school, teaching, and learning change? Central’s answer to that question would shape everything that followed.

If AI would soon be able to complete most traditional assessments, how should school, teaching, and learning change?

Summer 2024: Creating AI Guidelines

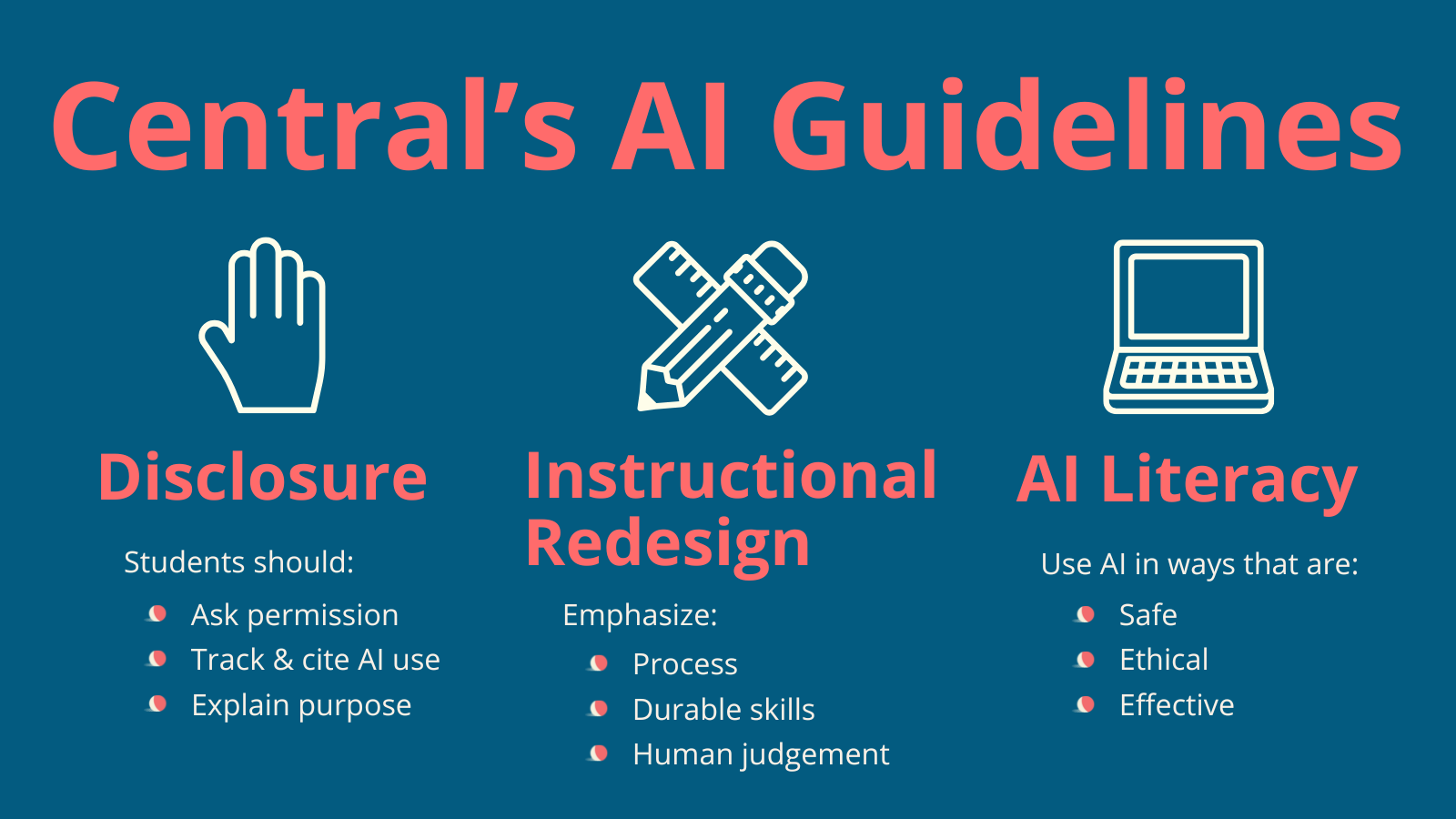

The superintendent convened a small task force that included a mix of teachers, students, parents, community partners, and representatives from the local community college. After important conversations about Central's mission and vision, they developed their first draft of AI guidelines, which featured the following commitments:

- Disclosure: Students could use AI with teacher permission for schoolwork, but they had to clearly explain how and why they used it.

- Instructional Redesign: Learning experiences and tasks should be redesigned to emphasize process, reflection, durable skills, and human judgment.

- K–12 AI Literacy: AI literacy would be prioritized for all teachers, staff, and students to help them use AI tools, when appropriate, in safe, ethical, and effective ways.

The guidelines went beyond compliance and academic integrity; they provided a map of Central's future and a clear signal that Central was dedicated to collaboratively shaping the impact of AI for their community.5

School Year 2024–2025: Central Under Pressure

The first school year felt less like cohesive implementation of the guidelines and more like chaotic triage of their impacts. The conflicts began in classrooms, where the guidelines' promise of "teacher permission" for AI use became a source of daily frustration. In one hallway, a history teacher proudly posted students’ AI-generated timelines and encouraged experimentation with research tools. Next door, an English teacher banned all AI use and required students to handwrite essays in class, citing concerns about authentic learning. Students moving between classes had to shift gears, because the tool praised in third period was grounds for discipline in fifth. The guidelines' requirement for "disclosure" of AI use created its own problems depending on the teacher and how they treated these disclosures. Students who honestly documented their AI assistance felt that in some cases they were judged or graded more harshly than peers who didn’t report their use.

Multiple students were accused of AI cheating, including some who hadn't used AI at all. A particularly painful incident involved a talented multilingual junior whose sophisticated writing voice led three teachers to suspect AI assistance. Despite the student's protests and her parents' outrage, the accusation followed her through the semester. The incident fostered a culture of fear and distrust. A growing number of students avoided AI entirely, while others hid all use.6

The contradictions from outside Central compounded internal tensions. The state promoted AI literacy frameworks developed by several organizations; meanwhile, statewide summative assessments remained unchanged. School board meetings regularly featured conflicting perspectives and pressure from both parents and board members to either accelerate AI adoption or pull back entirely. The superintendent found herself mediating increasingly heated conflicts about the fundamental purpose of education and the role of technology in schools.

Tense staff meetings included early adopters sharing new tools and AI successes while other colleagues pushed back, arguing that any AI use was educational malpractice. Staff shared anecdotes about students’ AI use and debated whether they were using the tools to support or undermine their learning. Some argued that building AI literacy and tool fluency was great in theory, but in practice it was leading students to develop new methods for shortcutting their learning. Skeptics pointed to examples of chatbot hallucinations and purpose-built AI tutors not scaffolding student learning. In response, AI supporters argued that this was part of the growing pains of innovating and preparing students for a future surrounded by AI-enabled tools. For them, AI’s issues offered learning opportunities for students that would help them navigate an uncertain future.

The superintendent found herself mediating increasingly heated conflicts about the fundamental purpose of education and the role of technology in schools.

Resource constraints created another layer of frustration. To ensure equitable access to technology, Central’s policy stated that students could access only free AI tools at school. This way all students had the same access. However, the gaps that teachers had observed the previous year, before Central’s guidelines, continued to widen. Students in higher-income households with paid access to tools continued to use AI in more complex ways. Teachers also observed that the most extensive users of AI were often students who had already been doing well in their classrooms.7 While students received the same AI literacy instruction and access in school, AI’s benefits weren’t equitably distributed.

A more troubling pattern emerged around student wellness. Counselors confirmed earlier reports that students had been using AI chatbots as emotional confidants. However, a few students had been forming dependent and even romantic relationships with AI companions, preferring their "always available, never judgmental" responses. While some students benefited from AI as a low-pressure way to practice social skills, others withdrew from human relationships.8

Teachers noticed or heard about students asking AI chatbots for advice on dating, family conflicts, and mental health concerns—areas where developmental support from trusted adults was crucial. Yet when counselors and administrators tried to investigate, they discovered that students were accessing these tools on personal devices and accounts, beyond the school's control or visibility. Parents and caregivers worried about AI systems providing unvetted advice to vulnerable teenagers, but some did appreciate that their children had an outlet for their feelings. News stories about self-harm and suicide fueled panic, and Central found that their AI literacy resources often narrowly defined safety in terms of privacy and security vs. the digital well-being of children.9

By February 2025, the superintendent faced a community fractured into camps. Some families demanded that Central "catch up" to tech-forward districts. Another group threatened to homeschool their children rather than subject them to "more AI indoctrination." School board meetings grew contentious, with public comment periods devolving into shouting matches about limiting vs. embracing tech. Many cited the trauma and negative impacts of distance learning during COVID or the impact of smartphones on students' mental health and learning. Several families moved their students to new private micro-schools, putting more pressure on the district’s bottom line. Teachers’ union representatives raised concerns about workload, evaluation criteria, and the fundamental changes to their professional roles. The "middle ground" that Central had always felt they occupied crumbled.

Each challenge reinforced the others in a vicious cycle. Resource constraints further limited Central's ability to respond effectively, and the guidelines published in August 2024 felt inadequate by spring 2025. Central needed a fundamentally different approach.

School Year 2025–2026: A Breakthrough Idea

As 2024–2025 ended, Central faced a critical choice: retreat to familiar approaches or double down on finding a path forward. The superintendent chose the latter, announcing in May 2025 that Central would create a lab school called the Innovation Lab.10 It would serve as a testing ground for new approaches to teaching and learning with AI that could be rolled out to the rest of Central. The superintendent was clear that the Innovation Lab wouldn’t avoid the hard questions; instead, it would seek answers through systematic experimentation.

Rather than appointing members to a new AI task force, the superintendent invited interested applications from across the district and community. By June, Central formed a 22-member team that included teachers, parents, students, administrators, and community partners. They also partnered with a local university to support the design and implementation of the Innovation Lab. The first meetings were tense, rehashing familiar debates, but a university facilitator helped the group move from venting to visioning.

The superintendent was clear that the Innovation Lab wouldn’t avoid the hard questions; instead, it would seek answers through systematic experimentation.

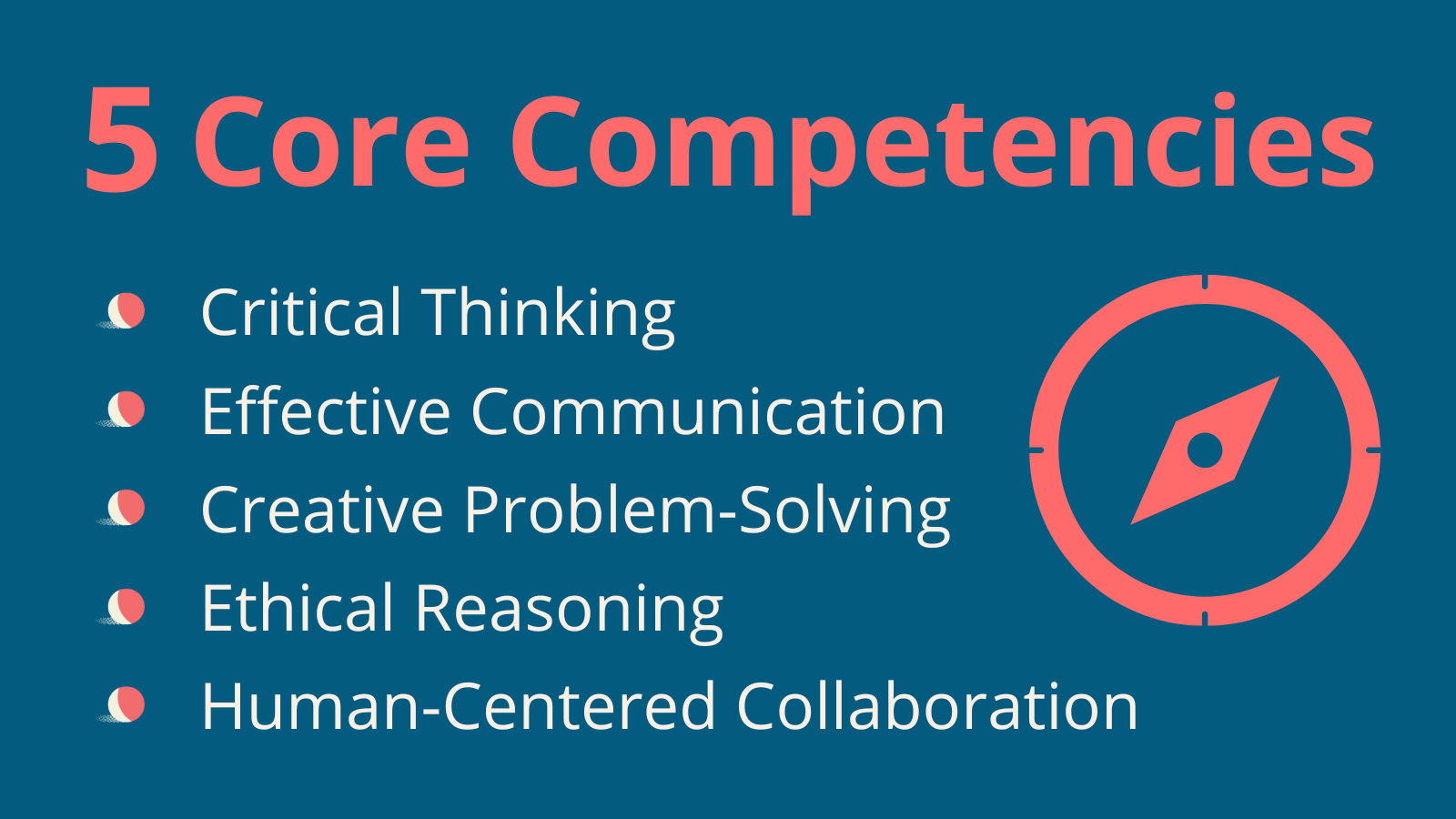

The Breakthrough

The breakthrough came once the group stopped debating whether AI was good or bad and started focusing on what students needed to thrive as learners and people. They identified five core competencies that transcended the AI debate: critical thinking, effective communication, creative problem-solving, ethical reasoning, and human-centered collaboration with technology. Preparing learners to develop these competencies and the durable skills, literacies, and mindsets necessary to achieve them became the North Star for the Innovation Lab's design.

The breakthrough came once the group stopped debating whether AI was good or bad and started focusing on what students needed to thrive as learners and people.

However, the district faced another challenge: Even with this clearer vision, the district's budget couldn't support some of the bolder changes advocated for by the Innovation Lab. Traditional funding formulas left no room for smaller class sizes, flexible scheduling, or extensive professional development. Consequently, the task force spent time thinking through how they could change school structure, curriculum, and staffing, and ways to fund these initiatives. They strategically decided to prioritize AI literacy and educator recruitment.

To supplement their incremental funding allocation from the district and make up gaps left by Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief (ESSER) funds, several task force members spent the summer and fall of 2025 submitting several major grant proposals. In the midst of grant cancellations and funding disruptions, Central managed to secure federal, state, and foundation grants covering three years of the Innovation Lab. These funds enabled flexibility in scheduling and teacher collaboration time and allowed them to hire specialists and allocate resources for curricular planning.

Teacher recruitment began in February 2026. Rather than assigning teachers to the Lab, the district invited applications from any certified teacher in Central. Thirty teachers applied for 12 positions. The selected teachers received intensive summer professional development and protected collaboration time in exchange for codesigning new approaches.

The Lab teachers leaned into the uncertainty. They committed to codesigning assessments in real time, documenting both successes and failures publicly, and accepting that the broader districts might reject their innovations.

The student and family recruitment process emphasized both opportunity and uncertainty. Information sessions and outreach in March and April 2026 presented the Lab honestly: Students would have access to cutting-edge tools and personalized learning, but they would also be part of an experiment. The district emphasized that students who needed better access to technology and tools at home would receive extra support.

Applications exceeded the allocated 300 student slots (150 middle school, 150 high school) by 40 percent, requiring Central to use a lottery system that prioritized a student body representative of the district at large.11

Procuring tools proved challenging. Two major AI companies offered the Lab free premium access, but task force concerns about data privacy, vendor lock-in, and corporate influence led Central to issue a comprehensive request for proposals (RFP) instead. Eight companies responded, and a three-month piloting process involving teachers, students, IT staff, and privacy experts revealed uncomfortable trade-offs. Educator-designed platforms had clunky interfaces, enterprise solutions were not interoperable with existing tools, free options lacked crucial administrative controls and accessibility for students with disabilities, and the most powerful, commercially available AI capabilities often came with limited safety and privacy protections.

After heated debate, the task force chose two companies. Central would partner primarily with their existing core education technology provider for institutional stability and key administrative and instructional functionality. Concurrently, they would use the Lab to pilot other tools from a start-up for advanced project-based learning applications. These partnerships gave all staff and students access to age-appropriate chatbots and tools with data-privacy safeguards in place.

Perhaps most challenging was building the evaluation and research infrastructure. The university partnership brought valuable expertise but also requirements. They designed baseline assessments of student skills teachers needed to administer, protocols for regular data collection, and systems for tracking both traditional academic outcomes and their five competencies (critical thinking, effective communication, creative problem-solving, ethical reasoning, and human-centered collaboration with technology). Teachers understood the need for this work, though it added one more thing to their full plates. Families raised concerns about privacy and safety issues, but they ultimately accepted the research requirements, having chosen the Lab specifically for its experimental nature.

Fall 2026: The Innovation Lab Experiment

After a busy summer of planning, recruitment, and procurement, Central launched its Innovation Lab School in fall 2026 with 12 teachers and a diverse group of 300 students, including students with disabilities and multilingual learners.

The Lab operated as a learning engine, not a boutique program. Its purpose was to discover approaches that other schools could adopt. Evidence of student learning and teacher approaches mattered. Oral defenses, process documentation, and portfolio artifacts ensured that AI use was visible, human-led, and reflective.12Parents and caregivers were given a regular window into the classroom and were involved in major decisions about technology and policy. The Lab committed to providing resources families could use at home to reinforce learning in classrooms.13 This at-home reinforcement extended to the AI literacy content, which was a component of every classroom and weekly routine via “bell ringer” discussions and carefully scaffolded, intentional, and reflective use of AI tools. Researchers worked directly with teachers and students to measure impact and share findings regularly with district leadership, school staff, and families.

Reactions from the community were mixed. Lab parents celebrated the real-world skill development they saw happening. One parent remarked at a school board meeting that his daughter was much more vocal about her learning in the evenings, walking him through things she had learned and how. A few Lab parents, however, grew concerned with the amount of AI use they saw, and wondered about striking a better balance between no-, low-, and high-tech usage. While local news stories about the Lab opened doors for ongoing relationships with several local employers, these same stories caused worry among parents whose children were not attending the Lab. They wondered if their kids were being left behind.

While the Lab had early successes, potentially scaling them to the rest of the district hit institutional barriers. The district's gradebook system couldn't accommodate portfolio evidence or competency-based grading, credit requirements demanded traditional seat time even when students demonstrated mastery, and state reporting systems captured test scores rather than the Lab's emphasis on process and reflection. Student performance on standardized state tests improved only marginally. Teachers questioned whether the district could sustain the collaboration time and flexibility the innovative work required and whether it was worth it, given the unremarkable test scores.

Teachers questioned whether the district could sustain the collaboration time and flexibility the innovative work required and whether it was worth it, given the unremarkable test scores.

Despite these challenges, by the holiday break some Lab practices did begin to spread in pockets throughout Central. A few months prior, Lab teachers had shared a set of structured thinking routines that teachers across Central could use with students to set responsible boundaries for their AI use. This helped to reduce tensions around AI disclosures and encourage transparency. A few pioneering teachers adapted the Lab’s "process-first" assessments, and a focus on competencies and durable skills became a key theme at departmental meetings. But resistance remained—some veteran teachers continued to balk at the disclosures and wondered if the regular AI disclosures and structured thinking routines truly prepared students for college. The spread of AI slop had humanities and visual arts departments increasingly resistant to AI literacy integration out of fear of students not developing their creative abilities. The Lab proved that new approaches were possible, but whether they were sustainable or palatable for the whole district remained uncertain.

Winter 2027: Progress and Pushback

The Innovation Lab started producing compelling, measurable outcomes. In class, teachers focused on balancing human and AI feedback and helping students critically evaluate the quality of AI feedback and outputs.14 Students demonstrated stronger metacognitive and durable skills and were more confident about what constituted responsible use of AI. Notably, incidents of student misuse or overuse of AI declined. Teachers reported higher engagement in project-based work, and students with disabilities and multilingual learners showed significant learning gains.15 There was a sense of relief when students’ writing scores on state assessments also improved, exceeding the minor gains of the previous year.

These successful practices required extensive professional development, flexible schedules, and extra time for teacher collaboration. Disjunctions persisted between the Lab’s assessment practices and the district’s systems and state policies. They became a growing source of frustration for Lab teachers. And while the Lab staff enthusiastically shared learnings with the broader Central community, a growing contingent of teachers across the district felt that they had “done AI literacy” already and complained about having to do yet another training. The Lab continued to prove its educational value, but its momentum was threatened.

External pressures intensified as AI was blamed, or even named by CEOs and industry experts, as the root cause of a poor job market for recent high school and college graduates. While there seemed to be an emerging demand for roles at the intersection of human and AI collaboration, parents and students kept seeing headlines and reports about the dwindling number of entry-level jobs available.16 School board meetings remained contentious as parents who claimed their own jobs had been lost to AI questioned why schools embraced the same technology. National and state policies pulled Central in several directions.17 Central’s broader student body did their best to navigate contradictory expectations, mastering some AI skills and then setting them aside for important assessments.

Conflicts boiled over when a deepfake video surfaced showing a school principal making racist and inflammatory comments about several students. The Lab demonstrated the value of AI literacy by quickly debunking the fake, but the incident surfaced tensions around the ethical costs of the technology that Central had adopted.

In response to the incident and new stories from other districts about deepfake revenge porn, the board reintroduced shelved proposals for surveillance and tracking systems, including some that used AI. Opponents worried that the proposed technologies, including AI-supported cameras and device-monitoring software, created “prison-like conditions.” When neighboring districts deployed similar surveillance tools, Lab students organized a forum and presented research on surveillance systems that revealed troubling patterns of false positives, unclear oversight, and gradual normalization of monitoring.18 Lab students argued that true safety came from trust and human connection, not algorithmic observation.

AI Surveillance in American Schools

By Jason Fournier

Due to increasing safety issues on K–12 campuses, schools have been making significant investments in security equipment and services. As of 2025, US schools make up a $3 billion market for these services, many of which already deploy AI (Caffrey, 2022). Companies like ZeroEyes and Volt AI monitor security camera video to detect weapons, while others, like GoGuardian, monitor students’ online activity. Given the increasing sophistication and proliferation of these technologies, we’re at a critical moment in the history of school surveillance.

The rapid expansion of surveillance technologies in schools has had troubling consequences. Data have shown that students with disabilities, students of color, and LGBTQ+ students are disproportionately flagged. Florida’s Polk County reported 72 involuntary psychiatric hospitalizations triggered by AI monitoring alerts over four years (Lurye, 2025). Surveillance systems have failed to detect weapons used in shootings, and false positives have resulted in student trauma. In one of these latter incidents, a 13-year-old girl was placed under house arrest and underwent a mandatory psychological evaluation after AI flagged an offensive joke (Blad, 2023; Burke & Schuppe, 2025; Lurye, 2025). In another incident, a student was flagged for writing about overcoming depression in a class assignment (Keierleber, 2020).

We’re at a crossroads that demands thoughtful, ethical action and decision-making. Since tools trigger contact with law enforcement, there’s a critical need for data on their validity and reliability. There’s also a need for frameworks that address fundamental questions around data ownership, intervention triggers, and the intersection of safety and discipline. The choice is clear: Either we will take full human responsibility, or we will hide behind algorithmic systems. Opting for the former risks creating an educational system that surveils rather than supports and monitors rather than mentors (Nichols & Monea, 2022).

Spring 2027: The Decision Point

The deepfake incident catalyzed community opinion and exacerbated existing divides. On one side, families demanded expanded AI literacy. On the other, families saw the incident as definitive proof that AI posed fundamental threats to truth and trust. Some of the parents who advocated for more AI literacy threatened to transfer their students to schools with more advanced AI programs if nothing was done.19 Parents on the opposite side, especially those in careers negatively impacted by automation, demanded a shift to job-related skills that couldn't be automated, like vocational and technical education programs. Central was caught in a new bind, not unlike the one that had given rise to the Lab.

Fast-approaching deadlines intensified the crisis. Budget decisions required board approval by May 1, and any major instructional changes would need summer planning. The state legislature was also considering new AI regulations that could override local policies, forcing Central to take a definitive stance before potentially losing local control.

Two new pressures converged:

Scaling Challenges: The Lab had shown promising educational benefits of thoughtful, effective AI integration in the classroom. Lab students’ response to the deepfake incident was evidence of this. However, to implement these practices across the entire system required changing the staffing model, restructuring schedules, and investing in the necessary professional development at a level not backed by existing budgets. Some argued for blending the successful elements that came out of the Lab’s experience into existing teaching structures; others warned that watering down the model would undermine its effectiveness, leaving Central stranded with old problems in the new reality.

Instruction and Assessment Misalignment: Classrooms had shifted faster than the standardized assessment structures connected to graduation criteria and measures of adequate academic progress. Federal policies encouraged AI integration in schools, while state policies held back more comprehensive changes to assessment, creating tensions around accountability measures and conflicting expectations. Employers asked for AI readiness, but colleges sent mixed signals about whether AI use in coursework would be accepted.

The challenges Central faced weren't just structural; they were about the district’s identity and the value their schools delivered for students and the community.

- Would Central roll back some of the changes they had made in favor of familiar approaches to restore academic rigor?

- Would they go all in on AI to try to maximize efficiency and optimize outcomes?

- Would they fully commit to a human-centered model that builds durable skills through a measured approach to technology?

Choose a Path to 2030

Make a choice for Central. Which of the three paths did they follow?

Editorial Note: The following narrative paths are designed to be more provocative than predictive. They’re meant to spur thinking and action, rather than chart the future. To this end, effects and transformation timelines have been compressed. In practice, paths will intersect, and some outcomes and impacts will emerge more gradually (e.g., four to eight years rather than two to three).

Path A: Return to the Fundamentals

What happens when AI moves underground

2027–2028: The Inevitable Retreat

The deepfake incident invited scrutiny across Central, and the pressure built for months. State reviewers questioned Central's portfolio assessments, citing scoring inconsistencies and equity concerns. While the Lab’s research had demonstrated improved writing scores and gains for students with disabilities, a state pilot study found that more AI-dependent students performed poorly on timed, unassisted exams. This study captured the attention of education media, which fanned concerns. Parents started questioning whether this would impact AP test scores and college admissions prospects. Three board members up for re-election publicly questioned whether innovation was worth the risk.

Then the startup Central had leaned on for project-based learning materials had a data breach. Thousands of student behavioral profiles were exposed, including disability documentation and family income data that parents were unaware was being collected. The incident revealed that Central's rapid AI adoption had outpaced its privacy safeguards—a legitimate concern that demanded a serious response.20 Lawsuits followed immediately, and the superintendent, facing termination, was pressured to walk back staff and student access to AI platforms, including at the Lab.

Central's rapid AI adoption had outpaced its privacy safeguards—a legitimate concern that demanded a serious response.

Over the course of the year, the practices that made the Lab unique were quietly abandoned. The Innovation Lab name existed, but what made it distinctive was hollowed out. Teachers’ extra planning and collaboration time was reassigned to covering other courses. District policies constrained both students and teachers to a minimal level of AI use, frustrating students and teachers who had developed fluency with AI. Students were restricted to using basic grammar-checking AI tools and tutors. Staff had to make do with a platform that generated worksheets, quizzes, and slide decks. As one teacher noted, "We went from AI-enabled learning back to AI spell-checkers." Portfolio assessments ended, replaced by weekly testing to "restore academic rigor."

Students felt the shift acutely, especially in the Lab. Many called it "going backward," given that they had engaged in more collaborative and AI-partnered problem-based learning and were now reverting to traditional teaching and assessment. But the restrictions applied only at school. At home, students with personal access continued using AI, but they did so without teacher guidance and the secure environment that Central had built to protect them. They used it to speed through homework assignments, generating written responses and problem sets they barely read, let alone understood. Students offloaded their thinking to AI tools without any checks in place. As one senior explained, "In the Lab, we learned to use AI to develop our ideas. Now I just use it to finish work I don’t care about faster." AI transformed from a thinking partner into a shortcut.21

AI transformed from a thinking partner into a shortcut.

In the meantime, state compliance reviews lasted two weeks, with observers scrutinizing every former Innovation Lab practice. The board unanimously adopted "traditional excellence" as Central's new mission. Lab staff struggled to understand how they fit in. Professional development shifted to test-preparation workshops, while counselors advised students to scrub their AI collaboration expertise from college applications. The rationale was clear: Prepare students for the world most schools understood—the world of standardized tests, college admissions essays, and traditional job interviews—rather than chase an uncertain future.

Board members argued that, by mastering “timeless fundamentals,” students could adapt to anything. Lab leadership and teachers were able to maintain a focus on skills building, persuasively arguing that critical thinking and communication were just as fundamental as math and literacy. However, academic outcomes took priority; the Lab had to show success on standardized tests. One board member who had initially supported the Innovation Lab captured the mood: "After the lawsuits and state pressure, we felt like we had no choice. Maybe we had moved too fast."

2028–2029: The Hidden Erosion

At first, the retreat seemed to be working for the Lab. Homework completion rates remained high, and assignments looked polished. Lab teachers felt reassured that students were adapting back to traditional methods.

But something was wrong.

Test scores began to slip. Not dramatically at first, just a few percentage points on unit exams or slightly lower quiz averages. Teachers saw it coming. While homework submissions were thorough and well written, when students sat for device-free in-class assessments, they struggled with basic concepts. Essays revealed shallow understanding and poor writing skills. Math tests showed that students couldn't work through multistep problems. Reading scores dropped. Teachers suspected hidden and uncritical AI use at home was to blame.23

This was a materialization of worries the Lab’s partner researchers and professional development providers had warned them about: Students were simulating rather than engaging in learning. By limiting teachers’ ability to structure and guide students’ AI use in classrooms, the conditions were set for students to offload their thinking and creativity to tools at home. As one junior admitted anonymously in a school survey, "I know I should do my homework myself, but it takes so long. Between theatre rehearsal and basketball practice, I don’t get home til 9:30 already. And everyone else is using AI too."

Frontier AI Labs and Learning Design

By Irina Jurenka

Education has emerged as a critical, high-stakes battleground for major frontier AI labs like Google DeepMind, OpenAI, Anthropic, and Meta (Fitzpatrick, 2025). Early research suggests that AI can improve learning outcomes when used in evidence-based ways, but eliciting such behavior isn’t easy and requires intentional design (Wang et al., 2025a). When pedagogical guardrails aren’t in place, models prioritize friction-free helpfulness (Huang et al., 2025). Such assistants function like a diet of sweets: They offer immediate gratification but strip away the productive struggle and cognitive effort essential for deep understanding (Young et al., 2024).

This design philosophy risks entrenching a "passenger mode," where students completely offload cognitive effort (Anderson & Winthrop, 2026; Gerlich, 2025). A stark divide is forming: A minority of self-regulated "explorers" will use AI to accelerate inquiry, while the majority risk intellectual atrophy and AI dependency (Anderson & Winthrop, 2026; Holt, 2024). Without intervention, we aren’t democratizing learning; we’re potentially widening the divide.

To correct this trajectory, we must shift incentives away from speed, scale, and user engagement and toward the delivery of high-quality learning experiences. We need a new infrastructure of robust evaluations and benchmarks that measure a tool’s impact on learners. Does AI encourage active engagement and productive struggle? Does it ignite curiosity and improve learning outcomes, critical thinking, and epistemic agency? This requires frontier labs working with the education community to establish best practices and efficacy. The objective is to design systems where the "broccoli" of hard cognitive work is compelling to learners—AI that refuses to do the thinking for us, and instead challenges us to think for ourselves.

Students privately called this "school brain." It was their survival mechanism. Recognizing the limited relevance of lessons and activities, they found themselves performing school’s traditional, routine tasks just well enough to get by. In their group chats they shared methods for using AI to sail through tedious work undetected.

Students were simulating rather than engaging in learning. By limiting teachers’ ability to structure and guide students’ AI use in classrooms, the conditions were set for students to offload their thinking and creativity to tools at home.

Surveys revealed that students were anxious about their future, and a majority of them felt that the Lab’s curriculum wasn’t relevant to their lives. An increasing number of students started missing school regularly. Enrollment patterns revealed that several wealthier families had pulled their children out of the Lab, choosing instead to send them to private schools.

Teachers felt powerless. The Lab had become a shell of its former self, and they felt their expertise was no longer valued or taken into consideration. An exodus began gradually, then accelerated. In the spring, five creative educators left in a single semester, along with the years of professional development invested in them. Exit interviews revealed a shared frustration about rampant, uncritical AI use outside of school, while in classrooms teachers had to focus on policing rather than improving use of the tools as they had previously.

2029–2030: The Reckoning

The full scope of the crisis became undeniable. Instead of rebounding, standardized test scores further collapsed. Central students' performance on state exams dropped to the lowest levels recorded. SAT and ACT scores fell sharply. Central schools that had once been recognized as innovative were now flagged by the state for academic intervention.

College acceptance letters told a devastating story. Due to low entrance exam scores, students who had maintained strong GPAs found themselves rejected from schools that had historically accepted Central graduates. Those who did gain admission faced a hard road. By winter break of their freshman year, nearly 40 percent of Central's recent graduates were on academic probation or taking remedial coursework. University advisors reported that most Central students struggled to write college-level analytical essays, solve complex problems independently, or use AI tools effectively in their coursework. They had developed neither the deep foundational skills their district had pivoted to emphasize nor the AI collaboration skills that colleges now expected. Lab students showed no significant deviation from these patterns.

The employer feedback was equally grim. Regional Medical Center's hiring manager noted, "Central graduates can't work independently or with AI assistance. They either try to do everything manually and fall behind, or they blindly accept whatever AI suggests without critical analysis. We need people who can do both." Local apprenticeship programs stopped recruiting at Central entirely. Entry-level positions that Central graduates had reliably filled for years now went to candidates from districts that had maintained structured AI integration programs.

The disconnect was painfully clear. Central banned AI to restore fundamentals, but students continued using the tools anyway. They did so poorly, secretly, and without guidance. They had been conditioned to use AI as a crutch for homework, then punished with tests that exposed their lack of understanding. The result was the worst of both worlds: students who could neither think independently nor collaborate effectively with AI.

Central banned AI to restore fundamentals, but students continued using the tools anyway. They did so poorly, secretly, and without guidance.

Despite the catastrophic data presented at quarterly board meetings, district leadership doubled down. The superintendent argued that the problem was insufficient rigor and enforcement, not the policy itself. "We need to crack down on academic dishonesty," the superintendent insisted, proposing even stricter technology monitoring and harsher penalties for AI use. But teachers knew there was no way to control a technology students had open access to outside the building. AI was impossible for students to resist, and Central could either teach students to use AI well or leave them to figure it out on their own. And with the Lab’s focus mostly eroding, Central would soon have no one to turn to for trusted guidance that could scale across the district.

By spring, local media coverage and declining student enrollment forced a reckoning. Parents organized. Teachers spoke publicly about the impossible position district policies had created. The board faced a stark choice between continuing down the path of prohibition or finding a way forward that neither ignored AI nor abandoned the core skills that still mattered.

The result was the worst of both worlds: students who could neither think independently nor collaborate effectively with AI.

The back-to-basics success story Central had hoped to tell had become a cautionary tale about what happens when schools respond to technological change with retreat rather than thoughtful integration. As one departing teacher wrote in her resignation letter, "We turned AI into a temptation that students had to face alone, and without the skills to use it wisely.”

Path B: Going All in on AI

The human costs of technology adoption and optimization

2027–2028: The Pragmatic Choice

Central's task force found themselves in the spotlight and faced mounting pressures from all directions. State reviewers were skeptical of Central’s evolved approach to assessment, media stories fanned concerns, and declining enrollment resulted in budget cuts that reduced teaching staff. The Innovation Lab showed some promising results and had strong advocates among Lab teachers and students. This data and community support successfully quieted some of the deepfake-fueled controversy and swayed Central’s community toward more tech-enabled approaches. However, scaling those practices would cost more than Central could afford. Adding to the pressure, several Central families had begun touring private schools that promised radical efficiency through AI-driven instruction—schools where students spent just two hours in physical classrooms, leaving most of the teaching, practice, and assessment to asynchronous, self-paced digital platforms and AI tutors.

At board meetings, parents increasingly asked pointed questions: "If other schools can deliver personalized education with AI tutors at half the cost, why can't Central?" The pressure to compete with these hyper-personalized models intensified when three families announced they were transferring their children, citing Central's "outdated approach" to technology integration. To prevent further losses, the superintendent presented a comprehensive AI platform. It promised to “modernize Central” and “leverage technology to enhance learning” through personalized, standards-aligned instruction, data-driven assessment, and efficient operations. The superintendent argued that the “best learnings” from the district’s successful Innovation Lab would now be scaled across Central.

However, in the superintendent’s presentations, it was clear to Lab staff that their mission had been misinterpreted. The Lab had positioned AI as a thinking partner for students, but the district drew a different conclusion. According to the superintendent, the Lab had shown that AI could be more than just a partner: It could be an effective teacher. The district-wide initiative she proposed would shift toward a more scalable and personalized approach enabled by technology and AI advances.

The Lab had positioned AI as a thinking partner for students, but the district drew a different conclusion. According to the superintendent, the Lab had shown that AI could be more than just a partner: It could be an effective teacher.

The initiative sparked some debate. Three board members questioned whether AI and algorithmic instruction could adequately replicate the accountability and encouragement provided by the student-teacher relationship. Supporters of the initiative argued that the Lab’s model was great but impractical, and Central’s financial reality left them no choice. The platform they had chosen to roll out district wide was designed to cut costs and increase efficiency. It promised automated lesson planning, instant assessment feedback, a tutor for every learner, and compliance reporting. Together, these tools would free teachers to spend more time with students. Everything would be “powered by AI” and therefore cutting edge. The vendor even provided reports from pilot districts that showed significant cost savings, primarily due to cut teaching positions.

Parents, still reeling from the deepfake incident from just a year prior, appreciated the platform's continuous-monitoring capabilities. The board highlighted the platform’s harm-detection algorithms and behavioral tracking, which would detect incidents before they escalated into a crisis. While a few parents strongly objected, for many the loss of privacy felt like a small price to pay for their children’s safety.

In the end, the board agreed it was their only viable path forward. They would adopt this new AI-powered personalized learning platform and shift to a new model where students spent most of the school day in an individualized learning pathway.

The Lab was no more.23

While the transformation began smoothly, points of friction and failure compounded. Early technical glitches left students locked out of lessons for hours, stretching IT staff thin and leaving teachers to troubleshoot and develop alternative plans to keep students busy. Data dashboards proved overwhelming and sometimes inaccurate, contradicting teachers’ observations. Students, including several with learning disabilities, found the automated feedback confusing and difficult to process. The system's comprehensive monitoring extended beyond academics to tracking movement, online activity, and behavioral patterns.

Disability Bias in AI Technology

By Nicole Fuller

Consider these experiences:

-

A dyslexic student takes a test with a virtual proctor, which is algorithmically designed to flag students for suspicious behavior that may indicate cheating. The student’s slow reading speed causes the technology to flag them for cheating (Brown, 2020).

-

A school purchases a new technology product required for all students, but it’s not compatible with a student’s screen reader, and they’re unable to use it.

-

A school district uses AI for job interview screenings. The eye movements of a visually impaired teacher result in him never getting to the interview stage of recruitment (Brown et al., 2020).

None of these technologies were sufficiently tested by people with disabilities or trained on their diverse needs and experiences. Tools trained on data for learners without disabilities may not adequately support learning for students with disabilities or diverse learning needs. In the research and development space, there’s a critical need to ensure that tools are accessible and avoid bias (Whittaker et al., 2019). AI adoption and use must include robust protections for student data while maintaining the data necessary to evaluate its efficacy, including how tools support students with disabilities.

For students with disabilities, their educators, and their families, the feedback loop is essential (McGee et al., 2025). Schools and districts must know how students are accessing technology and are responsible for any inequities in access (James, 2024). People with disabilities have long championed technology, while also asserting the principle “nothing about us without us,” signaling the need for inclusion in decision-making.

While most parents appreciated real-time notifications, some students found the monitoring invasive and uncomfortable. The parents of one student whose joke was flagged for self-harm contacted a child advocacy organization and formed a parent and caregiver coalition focused on resisting tech in schools. Teachers shifted more toward coaching roles. While they initially were able to increase one-on-one and small-group time with students, tech support became the primary focus of these conversations. Many teachers were surprised by how much they missed direct instruction.

Within months, some troubling patterns emerged around the AI platform's automated grading system. Students discovered they could game the algorithms. They could coast through content while adding key phrases to knowledge checks to boost scores. When teachers had the opportunity for in-class work, they noticed discrepancies between some apparently high-performing students and their actual understanding. The platform consistently marked down multilingual learners for "nonstandard" language patterns, even when their ideas were sophisticated and well reasoned.24 One chemistry teacher grew increasingly frustrated when the AI repeatedly marked correct answers as wrong because students used valid but less common problem-solving approaches the system didn’t recognize. Math teachers took issue with the finicky requirements for writing equations, and started to discuss how they might increase pencil-and-paper work.

The lack of transparency in grading criteria created deeper problems. Students received scores but didn’t understand them, making it nearly impossible for them to improve. Teacher dashboards showed student results but lacked essential data about how and why they arrived at their answers. This made conversations with frustrated students and parents difficult. Teachers found themselves defending grades they didn't assign and couldn't fully explain, eroding their professional authority and the trust students placed in assessment feedback. When families challenged grades, the platform provider cited "proprietary algorithms," leaving administrators unable to review or appeal decisions. The system promised efficiency, but it delivered a black box that removed human judgment from one of education's most consequential functions. Students could feel the difference between being evaluated by an algorithm and being understood by a teacher.25

Students could feel the difference between being evaluated by an algorithm and being understood by a teacher.

2028–2029: Embracing Automation

Despite the grading concerns, Central’s initiative addressed budget constraints and introduced perceived efficiencies that sustained momentum and provided just enough justification for deeper integration. State officials praised Central's seamless data integration and compliance. When the activity- and behavior-monitoring system flagged a safety concern and prevented a potentially serious incident, community support grew despite continued pressure from the contingent of concerned, tech-resistant parents and privacy advocates.

Due to continued issues with answer input and feedback, combined with a viral study demonstrating the negative impact of chatbot use for math learning, Central decided to switch back to an older intelligent tutoring system that had stronger research evidence. The resulting academic outcomes showed clear patterns. Students excelled best at structured problem-solving and procedural, rule-based tasks. Math and computer science scores increased substantially. However, teachers noticed concerning gaps in collaborative work and creative problem-solving. Students were optimizing responses based on what the AI tutor needed to hear to score their response positively rather than demonstrating their genuine understanding in their own words. When asked to tackle ambiguous problems outside of the tutoring system and without AI assistance, many students struggled to even begin. The collaborative model honed at the Lab, where students interacted intentionally and thoughtfully with AI to develop their ideas, had completely disappeared.

Students were optimizing responses based on what the AI tutor needed to hear to score their response positively rather than demonstrating their genuine understanding in their own words.

Division among teachers grew as the year went on. Data-focused educators worked around the limitation of the new analytics dashboards to target interventions, and given the larger class sizes, many teachers appreciated freedom from routine grading. However, teachers who valued their roles as content experts felt increasingly marginalized. When a veteran educator took early retirement after twenty years of service, she wrote to the board, "I became a teacher to inspire kids to think creatively and to love learning, not to monitor screens and troubleshoot."26

Families, too, were split over the changes and aired their grievances at board meetings. On one side, parents demanded fewer tools, more human instruction, and transparency in grades. On the other, parents defended the measurable results that the AI and intelligent-tutoring platforms delivered. What these parents didn’t know, however, was that the AI platform's algorithms recommended advanced courses more frequently to higher-income students than to lower-income students and students of color. This was uncovered by a teacher and guidance counselor at one Central’s high schools and subsequently solved district-wide, but only through manual work-arounds. When they contacted the vendor with the evidence, they promised a fix with no clear timeline.

2029–2030: The Algorithmic Future

Central continued to deliver strong outcomes, but their metrics felt increasingly outdated. State test scores reached district highs, even as the state board debated whether standardized tests designed for the pre-GenAI era still measured what mattered. The communications team highlighted these successes, but districts that were balancing these benchmarks with compelling stories of skills-building and AI mastery captured the spotlight.

It was clear that Central’s outcomes had concerning gaps that affected graduates’ preparedness. In the increasingly AI-augmented workforce, employers deeply valued collaboration and creative problem-solving skills. The Regional Medical Center reported that Central graduates followed protocols well, but couldn't adapt when patients presented unexpected symptoms requiring creative problem-solving. They had a hard time deviating from standard diagnostics and trusting their own logic and intuition. Tech companies noted that Central applicants could optimize individual tasks brilliantly, but couldn't work effectively in teams or adapt when projects required improvisation.

Students in four-year colleges and universities had equally mixed results. Students who majored in computer and information sciences tended to shine at solving well-defined problems, but faltered at teamwork and creative application in novel situations. Students in the liberal arts and humanities struggled to write lengthy analytical papers without AI support. Former Lab teachers pointed out to district leadership that the AI platform and tutoring systems created students who could excel individually and had procedural skill, but struggled to collaborate or make connections between knowledge domains. The result was deep knowledge with no creative spark.

A familiar incident later in the year reinvigorated critics of Central’s extensive monitoring of students. A student was joking with friends in a chat on her school device, and the system alerted local law enforcement to a safety threat. The student was arrested and released, but the incident revealed a pattern of false positives and trauma to students and families that was impossible to ignore. These concerns, coupled with graduates’ college and workforce challenges, raised questions for board members. What had Central gained in efficiency, but lost in humanity? Could students optimized by AI to excel on standardized tests thrive in a world that requires creative adaptation? Could the district reclaim the human elements of education without abandoning the accountability structures and efficiencies that now defined its success?

What had Central gained in efficiency, but lost in humanity?

During contract-renewal discussions with the platform provider, Central weighed the platform's undeniable benefits against mounting concerns. Despite initial hiccups, the system had overall maintained solid uptime and reduced operational costs while improving test scores. The vendor had also been responsive to feedback, implementing multimodal tools to make content and feedback more accessible to students with disabilities and multilingual students. The biased distribution of courses was on their roadmap, and Central was assured it would be fixed by back-to-school.

However, meaningful performance gaps widened, impacting the future of Central’s graduates. Students struggled with creative and collaborative applications of knowledge and skills. College-bound graduates complained that the work they had been doing was only marginally useful to success in their college courses. While they had a lot of experience with the district’s AI-driven platform at Central, they had very little experience using more off-the-shelf AI tools—the kind the Lab had specialized in piloting and exploring. Central’s students found they were good at following, but not steering, AI.

The students Central graduated were fundamentally different from those the district had once developed with the help of the Lab. The regional job market told the story clearly. Employers specifically requested graduates from neighboring districts for growth industry roles that required innovation and teamwork. Meanwhile, Central graduates found success in positions emphasizing technical execution and procedural skill.

The platform had delivered on its promises: measurable improvement, cost reduction, and behavioral monitoring. What it couldn't deliver, and what Central hadn't fully anticipated losing, was the messy, inefficient, and deeply human process of learning. They had traded away space in their classrooms for social experimentation where students could learn to think independently, create collaboratively, and adapt to uncertainty. In pursuit of a system that had all the answers, Central had failed to teach students how to ask the right questions. Central had optimized for the metrics the platform could measure while inadvertently diminishing the capacities it couldn’t: intellectual courage, creative risk-taking, and the ability to work with others toward solutions that didn't yet exist.

In pursuit of a system that had all the answers, Central had failed to teach students how to ask the right questions.

Path C: Redesigning School

Preparing students for perpetual change

2027–2028: Beyond the Binary

In addition to the controversies sparked by the deepfake incident, the superintendent and task force grappled with what to do in the face of shifting and competing policy priorities and students’ uncertain futures. State officials demanded traditional achievement metrics, while new federal programs promoted AI integration and invited a rethinking of assessment. Colleges sent mixed signals about portfolio applications, while employers increasingly expected AI fluency.

Rather than center their efforts on AI or technology, or fall back into the debates that characterized the initial task force work, Central decided to think more expansively. They started with a reflection on the competencies they had previously identified as their North Star: critical thinking, effective communication, creative problem-solving, ethical reasoning, and human-centered collaboration with technology. They asked themselves: If students were to truly master these competencies, what outcomes would they demonstrate? More importantly, what do students need to navigate the uncertainties of the future? To answer these questions, the task force developed a graduate profile that presented a new set of graduation expectations.27 This graduate profile identified student agency, adaptability, curiosity, an entrepreneurial mindset, and authentic human connection as high-priority outcomes, alongside success on traditional academic standards.

To navigate tension between federal encouragement and state restriction, they would adopt a “dual evidence” strategy. While they would continue to satisfy state accountability through testing, they would also pursue federal innovation grants to fund the portfolio-based assessment systems that truly measured students’ progress toward their graduate profile.

Rather than center their efforts on AI or technology, or fall back into the debates that characterized the initial task force work, Central decided to think more expansively.

The Innovation Lab's second-year progress added credibility to this ambitious vision. After reflection on their experiences and the research results, and through professional development and deep collaboration with the local university’s teacher-preparation program, Lab staff implemented an evolved instructional model. To meet the targeted graduate outcomes, the focus shifted to deepening core content understanding and building critical thinking, creativity, and metacognition competencies. When used, AI would be integrated intentionally and reflectively.28

The Lab also moved away from traditional structures like schedules with discrete subject courses and age-based leveling to more responsive, flexible learning pathways that balanced personalized and collective learning. These structural shifts enabled self-directed learning, interest-based projects, and collaboration that was more reflective of the real world and Central’s new graduate profile and target outcomes.

Lab teachers adapted the project-based learning platform to track schedules and manage interdisciplinary projects, carefully customizing AI integration and managing student data access. It worked well for a new entrepreneurship course required by the district that taught students how to identify problems worth solving and build creative solutions in collaboration with one another and AI. The core content platform was used primarily to boost students’ domain knowledge and skills for application in learning experiences that emphasized curiosity, student agency, and voice.29

AI as a Collaborative Partner

By Tanner Higgin

One common theme among the growing number of AI literacy frameworks, guidelines, and curricula is that AI should serve as a thinking partner for humans and that successful AI use should be and is collaborative (Casebourne & Wegerif, 2025; Chee et al., 2024; Chiu et al., 2024; Sidra & Mason, 2025). This opposes a vision of AI where tools and not humans drive learning, thinking, and creative processes. In practice, AI driving learning means students might look to chatbots for ideas and answers instead of feedback and support. Along the way, their ability to perform tasks themselves or critically analyze outputs could atrophy. This isn’t just a concern of educators, researchers, parents, or caregivers; students are worried about this too (Szmyd & Mitera, 2025).

While human-centered AI collaboration is widely desired, it's easier said than done. In practice, successful collaboration or systems for collective intelligence between humans, especially students, and AI can be difficult to structure, and there’s little firm evidence to turn to. The studies that have been conducted, many in psychology, have had mixed results and recommendations depending on the task, context, and working relationship between humans and AI (Cabitza et al., 2021; Fügener et al., 2022; Schmutz et al., 2024; Vaccaro et al., 2024). It doesn’t require research to know, however, that students need critical, social-emotional, and metacognitive skills to consistently evaluate their engagement with AI or that AI works best when augmenting rather than replacing teachers (Zhai et al., 2024; Holstein & Aleven, 2022).

Of course, all of this uncertainty is to be expected given the relatively recent rise of GenAI and the long timelines of rigorous research. In the interim, there’s a need for more exploration, testing, and sharing of what success for human and AI collaboration looks like, including in classrooms. This vision needs to be backed by practical frameworks that can guide usage and the creation of tools designed for successful collaborative engagement (Heyman et al., 2024).

To protect student privacy, Lab staff intentionally built safe, secure, and private digital environments for more extensive AI use and experimentation. In line with Central’s focus on intentional AI use, professional development explored how students could use AI as a tool to support and not replace their thinking and creativity. For this professional development, the Lab’s close partnership with the local university’s teacher-preparation program offered both evidence-based training and a recruitment pipeline.

Researchers found that after just two years in the Lab, students showed stronger critical thinking, adaptability, and engagement while also moderately improving their standardized test scores. The approach emphasized balanced human-AI collaboration. On the one hand, AI tools supported curricular planning, provided quick feedback, and recommended individual student-learning pathways. On the other hand, teachers led final instructional decisions, cultivated student relationships, and facilitated intentional tech-free periods of collaboration and learning.

To make sure that the Lab grew durable skills without a loss of academic readiness, the curriculum didn’t abandon core academic skills or content, or even more traditional tasks and assessments. Instead, this work was positioned as foundational for effective AI use. In fact, students still synthesized their thinking in essays and solved complex math problems without AI assistance. These activities built the skills students needed to fully benefit from collaboration with AI.

In fact, students still synthesized their thinking in essays and solved complex math problems without AI assistance. These activities built the skills students needed to fully benefit from collaboration with AI.

Lab graduates who entered apprenticeships now brought AI skills alongside their technical and analytical reasoning abilities. Local employers began to recognize that Central was producing graduates who could think for themselves and optimize their work with AI. Students who pursued four-year degrees got accepted to high-quality schools and found that at college they could balance their use of AI to support their studying and learning. College faculty praised Central students’ critical thinking, leadership, and communication skills. The Lab proved that thoughtful and measured AI-supported learning could satisfy the evolving demands of the education system and workforce, and that it was possible to shift the design of schools to make this learning authentic and relevant.

Based on this initial evidence, Central secured a federal grant designed for districts bridging traditional and innovative approaches to assessment. This would allow Central to expand proven Lab practices while still maintaining their “dual evidence” system, where students demonstrate learning through both conventional tests and portfolios.

Amidst all the positives, the Lab’s partner researchers did uncover one concerning data point. While teachers reported satisfaction with the curriculum and their preparation, a majority felt overwhelmed by all of the changes, and some teachers felt even more time-strapped than before. It was clear that a lot had been asked of the Lab teachers over the past two school years, and Central wondered if the gains for students would come at the cost of faculty burnout and lower retention.

2028–2029: Costs and Benefits

The Lab’s model attracted families who valued, at least in theory, the school’s combination of innovative practice, especially around AI, with a traditional, rigorous curriculum. In practice, familiar tensions emerged between those families preferring that the Lab emphasize one side over the other. Enrollment fluctuated as a result, and some families chose neighboring districts with more conventional schedules, course offerings, and pathways. A few even opted for homeschooling or virtual schools with more extensive and freewheeling use of AI. State reviews intensified, with officials questioning Central's portfolio assessments, even though they had received a federal grant in support of them.

The resistance proved costly. The Lab's model required extensive collaboration, time, and professional development that strained budgets, threatened (and sometimes disrupted) the work-life balance of teachers, and required teachers to shift from content deliverers to mentors. As Central had feared, some veteran educators departed to teach in districts with more familiar structures and expectations. Word spread, and recruiting became more challenging as neighboring districts offered more straightforward and less demanding AI-augmented roles.

Some of the tools the Lab adopted or created helped teachers manage the workload marginally better, but they were imperfect, and cognitive demands remained high. External pressures on Central mounted as standardized test companies publicly and loudly lobbied against alternative models like the Lab. The school board began criticizing the Lab’s approach as too expensive to scale.

Thankfully for the Lab and Central, success stories continued to emerge alongside challenges. While students questioned how they could meet the new standards for AI collaboration without overreliance, this friction was proof they had fostered the exact kind of AI literacy intended at the Lab’s founding. Regional employers who participated in employer partnership programs and visited for career fairs and talks praised Central’s thoughtful graduates. Lab alumni reported back to staff that their robust portfolios of work were a huge advantage in the competitive job market. Healthcare employers noted that the Lab graduates adapted faster to diagnostic tools and were the only new hires who critically evaluated the AI’s recommendations, spotting hallucinations and biases.30 Tech companies valued graduates' ethical reasoning and commitment to human-centered design. Lab students at four-year colleges and universities emailed some of their former Lab teachers, mentioning how they had become the AI gurus for their study groups. Central systematically documented this employer and university feedback, finding it more persuasive with state officials and the board than test scores alone.

While students questioned how they could meet the new standards for AI collaboration without overreliance, this friction was proof they had fostered the exact kind of AI literacy intended at the Lab’s founding.

2029–2030: A Resilient Model

Despite the controversies, Central's approach gained traction internally among schools willing to commit to flexible scheduling, an evolved approach to assessment and the graduate profile, and sustained professional development. These early adopters recognized that preparing students for an AI future wouldn’t be easy; it required resilience and a commitment to building the skills students truly needed.